Definition of mobile learning

| Definition of mobile learning | ||||

|

Mobile learning - as we understand it - is not about delivering content to mobile devices but, instead, about the processes of coming to know and being able to operate successfully in, and across, new and ever changing contexts and learning spaces. And, it is about understanding and knowing how to utilise our everyday life-worlds as learning spaces. Therefore, in case it needs to be stated explicitly, for us mobile learning is not primarily about technology. We find the definition by Sharples, Taylor and Vavoula (2007, p. 225) attractive, who view mobile learning as “the processes of coming to know through conversations across multiple contexts among people and personal interactive technologies”. However, we prefer to think of the processes of ‘coming to know’ to be located more broadly within communication which, we feel, rather thanfocusing more narrowly on the interpersonal, better captures the fact that meaning-making is bound up in economic, socio-cultural, technological and/or infrastructural systems including the mass media and technological networks/infrastructure. Sharples, M., Taylor, J. and Vavoula, G. (2007) 'Theory of learning for the mobile age.' In Andrews, R., & Haythornthwaite, C. (Eds.) The SAGE Handbook of E-learning Research. London: Sage, pp. 221-47 |

|||

Socio-cultural ecology

| Socio-cultural ecology | ||||

|

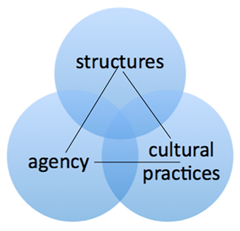

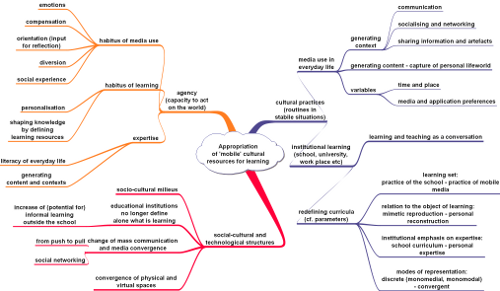

We see learning using mobile devices governed by a triangular relationship between socio-cultural structures, cultural practices and the agency of media users / learners, represented in the three domains. The interrelationship of these three components: agency, the user's capacity to act on the world, cultural practices, the routines users engage in their everyday lives, and the socio-cultural and technological structures that govern their being in the world, we see as an ecology which in turn manifests itself in the form of an emerging cultural transformation. The diagram is deliberately non-hierarchical, i.e. it can be read clockwise or anticlockwise and each one of the three branches of the concept map can be read first. It seems important to us that none of the domains is dominant over the other, and that their relative importance is determined by the specific context in which the model is used. Agency: young people can be seen increasingly to display a new habitus of learning in which they constantly see their life-worlds framed both as a challenge and as an environment and a potential resource for learning, in which their expertise is individually appropriated in relation to personal definitions of relevance and in which the world has become the curriculum populated by mobile device users in a constant state of expectancy and contingency (Kress and Pachler, 2007); Cultural practices: mobile devices are increasingly used for social interaction, communication and sharing; learning is viewed as culturally situated meaningmaking inside and outside of educational institutions and media use in everyday life have achieved cultural significance; Structures: young people increasingly live in a society of individualized risks, new social stratifications, individualized mobile mass communication and highly complex and proliferated technological infrastructure; their learning is significantly governed by the curricular frames of educational institutions with specific approaches towards the use of new cultural resources for learning. |

|||

Responsive contexts

| Responsive contexts | ||||

|

|

We are currently witnessing a significant shift away from traditional forms of mass communication and editorial push towards user-generated content and individualised communication contexts. These structural changes to mass communication also affect the agency of the user and their relationship with traditional and new media. Indeed, we propose that users are now actively engaged in shaping their own forms of individualised generation of contexts for learning. New relationships between context and production are emerging in that mobile devices not only enable the production of content but also of contexts. They position the user in new relationships with space, the physical world, and place, social space. Mobile devices enable and foster the broadening and breaking up of genres. Citizens become content producers, who are part of an explosion of activity in the area of user-generated content. But, sceptics might ask, is there a direct relationship between user-generated content and learning? Undoubtedly the link is currently still more obvious in certain disciplines, such as music, media studies etc, than others. Yet, if not planned for, failing to explore how educational institutions can cope with the more informal communicative approaches to digital interactions that new generations of learners possess, we argue, could lead to a schism between learning inside and outside of formal educational settings. We see the notion of 'learner-generated' as a paradigm shift where learning is viewed in categories of context and not content and as a potential. Learning as a process of meaning-making occurs through acts of communication, which take place within rapidly changing socio-cultural, mass communication and technological structures that we have briefly outlined above. User-generated context for us is conceived in a way that users of mobile digital devices are being ‘afforded’ synergies of knowledge distributed across: people, communities, locations, time (life-course), social contexts and sites of practice (like socio-cultural milieus) and structures. Of particular significance for us is the way in which mobile digital devices are mediating access to external representations of knowledge in a manner that provides access to cultural resources. This dynamic digital tool mediation of meaning-making allows users to negotiate and construct internal conceptualisations of knowledge and to make social uses of knowledge in and across specific sites or contexts of learning. |

|||

Appropriation

| Appropriation | ||

|

The second key issue is how learners appropriate mobile devices to set up specific learning contexts for themselves. How do they generate contexts for learning? Forming contexts with and through mobile devices outside of, as well as within existing educational sites of learning, we consider to be a key feature of appropriation. We see it related to the significant ongoing changes in terms of sociocultural practices and approaches to learning. |

|

| We define appropriation as the processes attendant to the development of personal practices with mobile devices and we consider these processes in the main to be interaction, assimilation and accommodation as well as change (Cook and Pachler, 2009; Pachler, Cook and Bachmair, 2010). Whilst clearly terminologically linked, these are not the same as the development stages that are described in Piaget's (1955) theory of development, which are sensorimotor, pre-operations, concrete operations, and formal operations. However, our work is aligned with Piaget's (1955) description of learning and perception as a constant effort to adapt to the environment in terms of assimilation and accommodation. Thus, assimilation in the context of learning means that a learner takes something unknown into her existing cognitive structures, whereas accommodation refers to the changing of cognitive structures to make sense of the environment. Furthermore, for us, the context of appropriation is emergent and not predetermined by events; centrality is placed on practice, which can be viewed as a learner's engagement with particular settings, in which context becomes 'embodied interaction' (Dourish 2004). We see appropriation as governed by the triangular relationship between agency, practice and structures. This inter-relationship manifests itself as emerging cultural transformations and appropriation provides a lens through which to view and analyse these changes. Indeed, we suggest that media convergence, together with the fluid socio-cultural structures of milieus and their respective habitus, lead to modes of appropriation as the individualised generation of contexts for learning. The spaces thus created differentiate everyday life into individually defined contexts as well as overarch different and divergent cultural practices such as entertainment and school-based learning. We envisage that at a foreseeable future point the sociocultural developments described above will lead to a situation where there is no longer a need for a differentiation between media for learning inside and outside formal educational settings. Our notion of appropriation also provides a conceptual frame to understand the growing gap between the literacy practices outside and inside formal educational environments. By 'literacy practices' we refer here to the cultural techniques involved in reading and producing artefacts to make sense of, and shape the sociocultural world around us. The key point is that learners are evolving practices and meanings in their embedded interactions, i.e. interactions embedded in cultural artefacts that are found outside formal learning systems. A key challenge is to support learning between and across contexts outside and inside of educational institutions. To do this as educators, we need to make use of emerging cultural transformations that mobile devices afford and bring about as well as of the resultant cultural products that enable the individualised generation of content and contexts for learning. In short, “appropriation is a generic term governing

all processes concerning the internalization of, and externalization into

the pre-given world of cultural products across the breadth of learning

in educational institutions and in everyday life. Appropriation and the

pre-given world of cultural products work as context of development and

are indispensible for the development of human beings. Today, everyday

life works as a dominant context of development and is tied up with media

use, notably the use of mobile devices, governed by structures of mass

communication. Learning and media use, as modes of appropriation, are

cultural practices which are determined inter alia by the agency of the

user, such as her habitus of media use and of learning. Appropriation

links curricular practices with child development, which take place in

a context of social, economic, cultural and technological transformation,

with children developing their inner capacities by internalizing cultural

resources including those artefacts made available by and through, and

created with mobile devices.” |

||

At-risk learners

| At-risk learners | ||||

|

|

Mobile and individualised mass communication has reached all social strata and milieus. One educational challenge for the school is to deliberately identify the thematic conversational threads of those milieus that are at a distance to the school. There exists a real risk that some milieus are unable to benefit from the resources society has to offer but which are essential for responsible and successful living in modern, individualised life-worlds. Mobile devices possess an inherent potential for cultural participation as they are integrated into two main socio-cultural structures: media convergence and socialcultural stratification. A complex expertise is necessary to be able to act within these structures. As a phenomenon of everyday life, the mobile complex is clearly segregated from school but the school contributes important competences, among others the ability to read and write. At the moment the school seems to deliberately seek a segregation between itself and learners' life-worlds. Banning mobile devices from school is an indicator for such deliberate segregation. Many young people, especially male adolescents with migrant backgrounds from the so-called hedonist milieu, do not have the intention to match their life-world expertise to that required in school. Looking at internet video platforms we can see that a lot of homework is produced by means of the mobile phone (see e.g. http://de.youtube.com/group/MathTutor). This indicates the at-risk learners' personal, and the school's institutional practice of segregation is not the only possibility. To overcome the segregation of the mobile complex and the cultural practices of schools, our proposal is to adjust school to the practices, agency and structures of the mobile complex. We emphasise the proposed assimilative procedure of docking the school onto responsive mobile und user-generated contexts. One important reason for doing so is that these contexts work as 'zone of proximal development' in a Vygotskian sense. Furthermore, the school can take up conversational thematic threads, which are laid out by students in their personal media use. We try to identify conversational threads of identity and expertise, which the school can take up in order to assimilate the competences evidenced by the young man in the process of taking and uploading the video into the school. In our socio-cultural ecology, we define mobile devices as cultural resources in the hands of 'at-risk' learners. By 'at-risk' learners we mean young people who are underachieving in terms of the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) in the area of literacy, i.e. reading and writing. We clearly do not infer any lack of intelligence or competence but simply draw attention to the question of their resources not being validated by school and society or them not wanting to utilise the resource valorised by society. |

|||